A Daughter of the Middle Kuskokwim

Rebecca Wilmarth of Donlin Gold Fights for Community Resilience

Storyknife, May/June 2023 edition

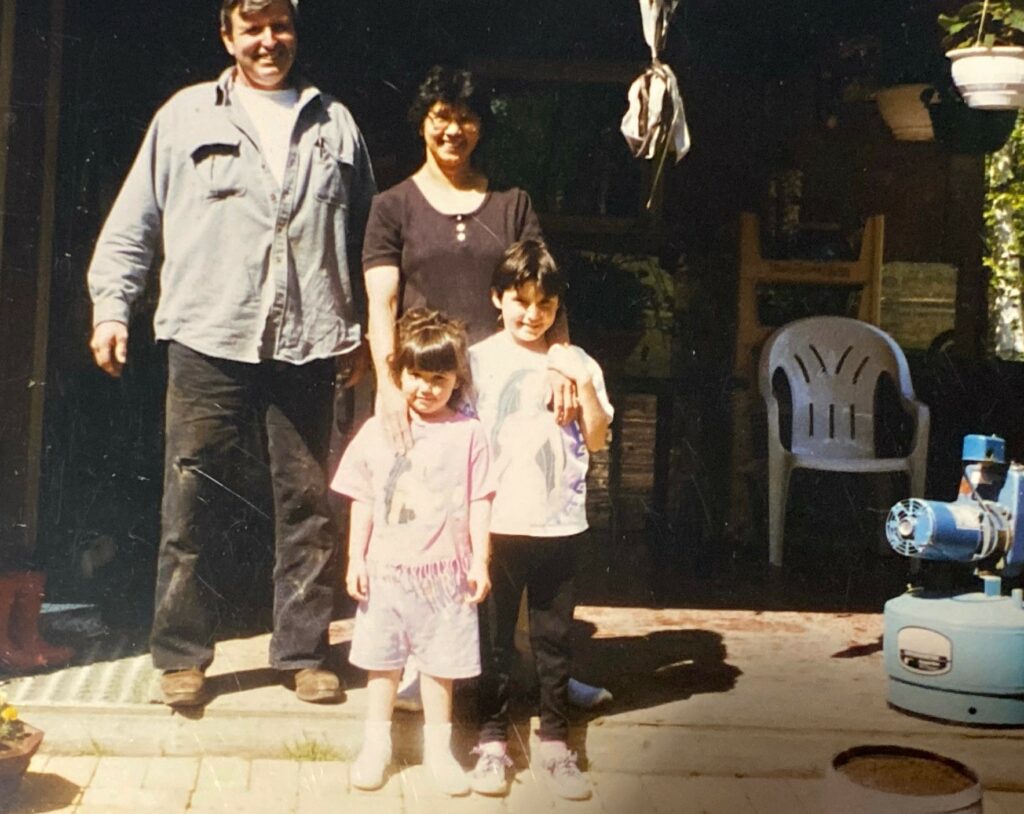

Rebecca Wilmarth (bottom right) with her sister and parents in Red Devil

For Rebecca Wilmarth, the subsistence way of life and mining are comingled in her blood.

Born to an Athabascan-Yup’ik mother and a placer miner who raised their children along the middle Kuskokwim, Wilmarth wants to see that kind of lifestyle revitalized.

“Looking back now, I realize I grew up in the best of both worlds. If our region had more opportunities, our people wouldn’t have to sacrifice their homes or lifestyle on the river,” says Wilmarth, a Calista Corp. Shareholder, tribal member, wife and mother of two.

Continuing the way of life practiced by many generations of Shareholders is a big part of why Wilmarth supports the Donlin Gold Project, as she explained in this interview for our annual report.

Q: WHAT WAS IT LIKE GROWING UP PLACER MINING AND LIVING IN MIDDLE KUSKOKWIM VILLAGES?

A: I was born and raised in Red Devil, one of the smallest villages on the Kuskokwim River. I went to grade school in Red Devil and spent most of my childhood summers at the family mining camp near Flat. I also spent a lot of time in Georgetown with my grandparents, who were avid gardeners.

My mom’s side is from the Georgetown, Red Devil and Sleetmute area, and I feel grounded there, at home with my people. My dad exemplified the importance of hard work; his words ingrained in my mind—that a wishbone isn’t as likely to get you someplace as a backbone. Some of my earliest memories are of watching my dad operate his dragline and helping my mom sell candy bars in their store. Working hard every day seemed fun to my parents, so naturally, that’s how I feel about it today. I’m lucky to have grown up the way I did.

Rebecca and her husband Corey Nicholai moose hunting on the Holitna River in 2021.

Q: WHAT IS YOUR EXPERIENCE OF OUTMIGRATION?

A: I’ve primarily lived my whole life in Red Devil, and the population there started to dwindle quite rapidly in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The school was always on the verge of closing, and my parents decided to relocate to Palmer, where my siblings finished school. I went to school in Aniak for three years but decided to return to my family and received my diploma via home school.

When I started working for Donlin, it meant job security, something that isn’t common in our village. But with our kids, the educational thing became more of a priority for us, so we live in Palmer during the winter. It’s been positive for us—for school and sports—but I’m also feeling the disconnect.

Q: WHAT OTHER CHANGES ARE YOU SEEING ON THE RIVER?

A: I remember lots of travelers on the middle river when I was growing up. People were out and about, visiting, hunting, attending community events.

There is a lot less of that now. I think fewer households are able to do subsistence activities. It’s a combination of fuel costs and the impact of fishing shortages and regulations related to conservation efforts. A lot of people don’t have the means to go out and do what they used to do.

For Red Devil, it was a domino effect after the school closed in 2009. I just heard last week the Stony River school is closing, and I feel for them. I wish I could reverse it. What we hear sometimes is that Donlin will ruin the subsistence way of life. Well, it’s happening already, and it’s not related to Donlin.

If I had to choose between Donlin and being able to fish or hunt or otherwise subsist, then I wouldn’t be here. We can have both.

Rebecca Wilmarth

Q: HOW DID YOU END UP WORKING FOR DONLIN AND WHAT DO YOU DO?

Rebecca and her husband Corey Nicholai.

A: I went to work for my tribe, Georgetown, right after high school, and from 2006 to 2010, I was the tribal liaison out of the Anchorage office, working as a link between the office and tribal members.

I realized I needed to do more to solve some of our issues. I moved back to Red Devil and began taking classes in rural development through the University of Alaska Fairbanks. My husband Corey and I lived

in Red Devil and did whatever jobs we could to stay there. He worked at the runway, I worked at the post office, and we ran a fuel business.

I always envisioned Donlin as my ultimate career. I knew that if meaningful employment was available in Red Devil, I could provide for my family and not have to leave home. In 2019, after I graduated with my degree in rural development, Donlin asked about my interest in working for the company. I was completely floored and said yes, definitely.

This will be my fourth year at Donlin, and I’m now the Community Relations supervisor. I appreciate the vision they’ve had for me as I continue to grow in my role with the company. The most rewarding aspect of the job is talking to people in the region and connecting them with good information about the project.

Q: DONLIN IS CONTROVERSIAL. WHAT DO YOU WANT SHAREHOLDERS TO KNOW?

A: I try to break down the notion that Donlin is some big corporate glob. A lot of us in Community Relations are from the region and we are stakeholders, too. We have the same concerns.

There are real concerns and fear out there. I try to share my life experience and perspective, and let people know their questions or concerns can be heard and valued, and we’re not a Canadian company driven by money.

Our villages have a long road ahead in terms of capacity-building and sustainability. I like to think of Donlin as being a good neighbor who can help get them there. You can call and talk to any one of us, and you’ll always get our full attention and care. The vision I have for our people and villages is that they are prospering economically, socially, and culturally.

Rebecca Wilmarth berry picking near Red Devil.

Q: HOW HAS WORKING FOR DONLIN INFLUENCED YOUR LIFE ON THE RIVER?

A: Meaningful income complements a traditional lifestyle rather than detracts from it. In the summer, we are out in the boat as soon as the ice goes out—early to mid-May—fishing for sheefish and logging. When it’s time to put up fish for winter, my family comes out from Palmer. All of the kids are part of the process from start to finish. In the fall, my husband and I love to hunt, and we hunt for other people who aren’t able to get out and hunt themselves. In the winter we’re out ice fishing and hauling wood—not this year, unfortunately. I don’t take any of it for granted.

Me, personally, if I had to choose between Donlin and being able to fish or hunt or otherwise subsist, then I wouldn’t be here. We can have both.